Echocardiography

Brief Communication

Echocardiography in the Chinchilla

Annika Linde, Nuala J. Summerfield, Matthew Johnston, Tonatiuh Melgarejo,

Angela Keffer & Evelyn Ivey

Annika Linde, Nuala J. Summerfield, Matthew Johnston, Tonatiuh Melgarejo,

Angela Keffer & Evelyn Ivey

Heart disease has been described in the chinchilla and, with increasing popularity as a pet, the demand for diagnostic evaluation and treatment has increased. The goal of this study was to determine normal values for echocardiographic measurements in chinchillas and the effect of anesthesia on these measurements. Seventeen clinically normal adult chinchillas were studied. All animals were anesthetized with isoflurane by mask. Standard echocardiographic views were used. A difference was seen in the echocardiographic measurements for left ventricular systolic dimension (LVIS), fractional shortening (FS), aortic diameter (Ao), left atrial diameter (LA), LA/Ao ratio plus peak flow velocities (PFVs) and ejection times (ETs) for Ao and pulmonary artery (PA) flows between awake and anesthetized chinchillas.

Key words: Diagnostic imaging, heart disease

The chinchilla shares many anatomic and physiologic characteristics with the guinea pig (a well described laboratory animal), but the amount of scientific data on the chinchilla is limited. Due to increasing popularity as a pet, the need for more scientific information on this species is warranted. The chinchilla is presented frequently with a variety of diseases, including cardiac disease. The present study was conducted to determine normal values for echocardiographic measurements in normal chinchillas in order to make diagnostic evaluation using echocardiography feasible in this species.

Material and Methods

The present study was conducted at the University of Pennsylvania’s Small Animal Veterinary Teaching Hospital. Seventeen clinically healthy chinchillas, 9 males and 8 females, owned by a local chinchilla breeder were included in the study. Pedigrees were not available, and the extent of relationship among animals is not known. All animals were weighed and physical examinations were performed.

Animals were included in the study only if the physical examination was unremarkable. Animals were evaluated echocardiographically twice over 2 days (with a 4 week interval), first while anesthetized and secondly while awake. The studies were performed by 2 individuals with specialty training in cardiology (AL, NJS). Each person performed half of the echocardiographic examinations on each of the 2 days, but both echocardiographers were present during all examinations. Each measurement was based on an average of 3 examinations. According to the anesthesia protocol, chinchillas were induced by using an airproofed box with direct administration of 5% isoflurane, and afterwards switching to a mask with 1-3% isoflurane for maintenance. Twenty minutes or fewer were used on the echocardiographic examination of each chinchilla (including induction of anesthesia). Each animal was placed in right lateral recumbency for the echocardiographic examination. A Hewlett Packard 5500 with a 12 mHz probe was used for the echocardiographic examinations at a depth of 2-3 cm. Standard echocardiographic measurements were obtained using standard views1. Ao and mitral valve (MV) Doppler flows were optimized using the left apical view, with animals remaining in right lateral recumbency. The initial sample size included 20 animals. Three animals were excluded due to detection of heart murmurs on the initial physical examination. Animals with murmurs were evaluated echocardiographically, but excluded from the actual study data.

Data was analyzed using a Student’s t-test, assuming a Gaussian distribution, at a 5% level of significance. All data passed a normality test. A paired t-test was used for comparison of differences between the awake and anesthetized states, and an unpaired t-test was used to compare possible differences in the statistics between sexes a.

Results

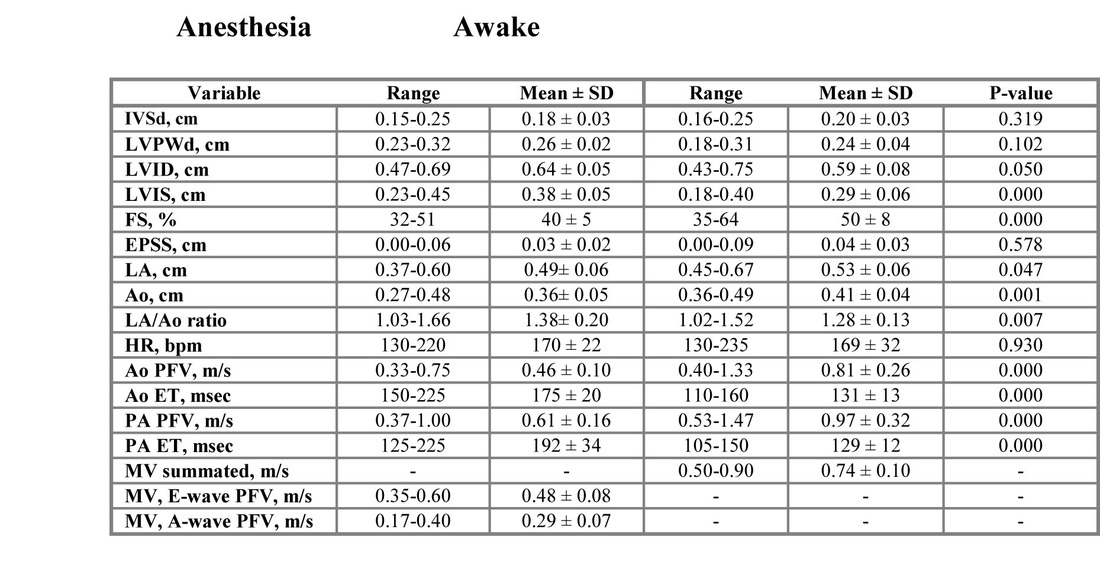

The echocardiographic measurements are listed in Table 1 (n = 17). Results are expressed as mean ± SD. A statistically significant difference in the body weight was found between sexes, with females having a higher average weight (681 ± 145 g vs. 615 ± 119 g, P =0.041). In the anesthetized chinchillas, no statistically significant difference was found between sexes for all echocardiographic measurements with the exception of LA diameter, including LA/Ao ratio. In the awake chinchillas, no statistically significant difference was found between sexes for all echocardiographic measurements, with the exception of the LA/Ao ratio. Comparison of each echocardiographic measurement for all animals while anesthetized and awake (P-values, Table 1) showed statistically significant difference in LVIS, FS, Ao and LA diameter, LA/Ao ratio, and PFVs and ETs for Ao and PA flows. MV inflow was summated in all awake animals. Heart rate did not differ significantly between the awake and anesthetized states.

Statistically significant results for anesthetized animals were as follows: LA diameter in males was larger than in females (0.46 ± 0.05 cm vs. 0.53 ± 0.05 cm, P = 0.010). LA/Ao ratio in males was larger than in females (1.49 ± 0.17 cm

vs. 1.25 ± 0.16 cm, P= 0.010). Statistically significant results for awake animals were as follows: LA/Ao ratio in males was larger than in females (1.34 ± 0.12 cm vs. 1.21 ± 0.12 cm, P = 0.037).

The 3 animals with murmurs were evaluated echocardiographically but not included in the data set. One animal had MV insufficiency and abnormal myocardial appearance. No specific changes were detected in the Doppler flow for the remaining 2 animals with murmurs, and we assume these were flow murmurs.

Discussion

Certain types of cardiac disease such as dilated cardiomyopathy, congenital septal defects and valvular disease have been reported in the chinchilla b. Murmurs of varying intensity have been described in chinchillas, and often are found on routine examination of young animals 2. No scientific reports presently are available on the prevalence of various heart diseases in this species, and the relationship between the occurrence of heart murmurs and underlying cardiovascular pathology has not been investigated in the chinchilla 3. One case of a ventricular septal defect and concurrent mitral valve dysplasia confirmed on necropsy has been described in a 2-year-old male chinchilla that died suddenly during its daily activity period2. In order to diagnose pathology it is necessary to recognize normal anatomy. The present study was conducted in order to determine normal echocardiographic measurements for chinchillas. Based on these findings, abnormalities can be evaluated, and a diagnosis of cardiac disease made on a more scientific basis. Early myocardial disease, however, still may be difficult to diagnose even by use of echocardiography.

In this study, LA diameter and LA/Ao ratio when measured while animals were anesthetized and awake differed between sexes. The mean LA diameter was relatively larger in males than in females, which was unexpected because females had a larger average body weight. No reason for this finding was evident.

A statistically significant difference was seen between anesthetized and awake animals in regard to LVIS, FS, Ao and LA diameter, and PFVs and ETs for the Ao and PA flows, which may be attributed to the effect of the anesthetic agent in this species. The cardiovascular effects of isoflurane to our knowledge have not been investigated in the chinchilla. Isoflurane is used in mice during

echocardiography and generally produces only minimal cardiac depression4. In dogs stroke volume, total peripheral resistance, and left ventricular work tend to decrease with increased depth of isoflurane anesthesia5. Myocardial function is well preserved during isoflurane anesthesia in normal children6.

Animals were evaluated on 2 different days, and by 2 different echocardiographers. These factors may have contributed to the differences seen.

MV inflow appeared to be separated into distinct E- and A-waves on the chinchillas while awake, and summated while under anesthesia. Anesthesia may have altered diastolic function and flow characteristics independently of heart rate, because these findings were basically unchanged, but this interpretation remains speculative.

No reports on heart disease in the chinchilla have been published to our knowledge. This report therefore is the first to provide data on guidelines for echocardiography in this species. Consequently some of the animals included in the present study may have been falsely considered normal. In order to minimize this error we excluded any animal with a detectable heart murmur. An obvious limitation of the study is that the number of animals is quite small. Also, all chinchillas came from the same breeder, which is less ideal than studying unrelated animals.

The effect of anesthesia could have been confounded by the order in which the 2 sets of examinations were completed. For practical purposes, we did not randomize the order of examinations, but instead performed the examinations over 2 separate days. The 2 examination days, however, were separated by several weeks. Consequently, even though the duration of isoflurane’s effect on echocardiographic variables still is unknown in the chinchilla, it is assumed that any possible remaining amount of the drug must be small after this period of time and therefore should not substantially affect the results.

Echocardiography appears to be a diagnostic tool that can be successfully applied to the chinchilla. As in any other clinical situation, it is important to evaluate the complete clinical picture and possibly use other diagnostic tests.

Echocardiographic measurements in this group of clinically normal chinchillas hopefully will help validate future diagnostic imaging of the heart in this species.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge The Chinchilla Health Information Network for funding this project, and Mr. Dave Woods, Whitewoods Chinchillas, Pennsburg, for providing the animals for the study.

References

1. Thomas WP, Gaber CE, Jacobs GJ et al: Recommendations for standards in transthoracic two-dimensional echocardiography in the dog and cat. Echocardiography Committee of the Specialty of Cardiology, American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine. J Vet Intern Med, Jul-Aug;7(4); 1993:247-52.

2. Hoefer HL: Clinical management of the chinchilla & hedgehog. In: Proceedings of The Avian/Exotic Animal Symposium. Davis, CA, School of Veterinary Medicine at the University of California; 1966: 87-91.

3. Donnelly TM, Schaeffer DO: Disease Problems of Guinea Pigs and Chinchillas. In: Hillyer EV, Quesenberry KE, eds. Ferrets, Rabbits, and Rodents – Clinical Medicine and Surgery. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 1997: 278.

4. Roth DM, Swaney SS, Dalton ND et al: Impact of anesthesia on cardiac function during echocardiography in mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiolo 282, 2002: H2134-H2140

5. Steffey EP, Howland D Jr: Isoflurane potency in the dog and cat. Am J Vet Res, Nov; 38(11); 1977: 1833-6

6. Wolf WJ, Neal MB, Peterson MD: The hemodynamic and cardiovascular effects of isoflurane and halothane anesthesia in children. Anesthesiology. Mar; 64(3); 1986:328-33

Footnotes

a: SPSS for Windows, Version 11.5.1, ©SPSS Inc.1989-2002

b. Ritchey L, Cogswell M: The Joy of Chinchillas, 3rd ed. Menlo Park, CA (privately printed), 1995.

From the Department of Clinical Studies, Sections of Cardiology and Special Species, School of Veterinary Medicine, Small Animal Hospital, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA.

Dr. Linde is presently affiliated with Texas A & M University, TX. Dr. Summerfield is presently affiliated with The University of Liverpool, UK. Dr. Johnston is presently affiliated with Colorado State University, CO. Dr. Melgarejo is presently affiliated with Kansas State University, KS.

Part of the data was previously presented as an abstract at The American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine Forum, Dallas, TX, 2002

Table 1: Echocardiographic measurements for a group of clinically normal chinchillas (n = 17)

Abbreviations

IVSd: inter ventricular septum in diastole

LVPWd: left ventricular free wall in diastole

LVID: left ventricular diastolic dimension

LVIS: left ventricular systolic dimension

FS: fractional shortening

EPSS: E-point septal separation

LA: left atrium

Ao: aorta

HR: heart rate

PFV: peak flow velocity

ET: ejection time

MV: mitral valve inflow

IVSd: inter ventricular septum in diastole

LVPWd: left ventricular free wall in diastole

LVID: left ventricular diastolic dimension

LVIS: left ventricular systolic dimension

FS: fractional shortening

EPSS: E-point septal separation

LA: left atrium

Ao: aorta

HR: heart rate

PFV: peak flow velocity

ET: ejection time

MV: mitral valve inflow